Students exercised by decolonisation show us a new way of opening out English studies

Elleke Boehmer

This piece was first published in the Times Higher Education supplement, 2 May 2019, pp. 42–3. Read the full THE feature on the state of English Studies here.

Ask many UK English literature academics a question about the future of the discipline and they will turn their eyes skywards in exasperation and despair. Numbers of applicants to most English studies degrees are falling. And while the removal of the cap on student numbers in 2015 has allowed some departments to stem the decline, the knock-on effects have also only hastened it elsewhere – prompting regular worried huddles over the departmental coffee machine.

Target grades are lowered, but still courses are closing down – and so, inevitably, jobs are under threat. English literature, one of the most popular areas of the humanities until very recently, now struggles in particular to attract male students, and those from ethnic minorities especially. There are no jobs in studying English, I hear again and again from my students, even at a privileged institution such as mine. How, they ask, does reading books prepare us for careers in the real world? How do these long poems you prescribe set us up to deal with pressing social issues in the ways that “real disciplines” like law or even history do?

As if these were not body blows enough, in recent times the subject has been hit by a further set of challenges from a different direction. However, I’d like to suggest that these represent more of an opportunity than a matter of concern. Approached as a prompt genuinely to consider how English studies might matter (or matter again) to today’s young British readers, they provide us with a way of refreshing – if not completely overhauling – our subject and mode of textual interpretation. And this could be a really good thing.

I am speaking, of course, of the actions and questions generated by the loosely related “decolonial” movements that have emerged since 2015, including “Why is my curriculum so white?”, Black Lives Matter and Rhodes Must Fall. And while their reach has been cross-disciplinary, the English students involved have invited us to ask fundamentally important questions about what might be called the diversity of our syllabus, and the representativeness of the texts we teach.

Many students feel that they cannot ‘find themselves reflected’ in standard ‘Englit’ course content. Even in 20th-century courses, there are not enough texts by black and other minority writers

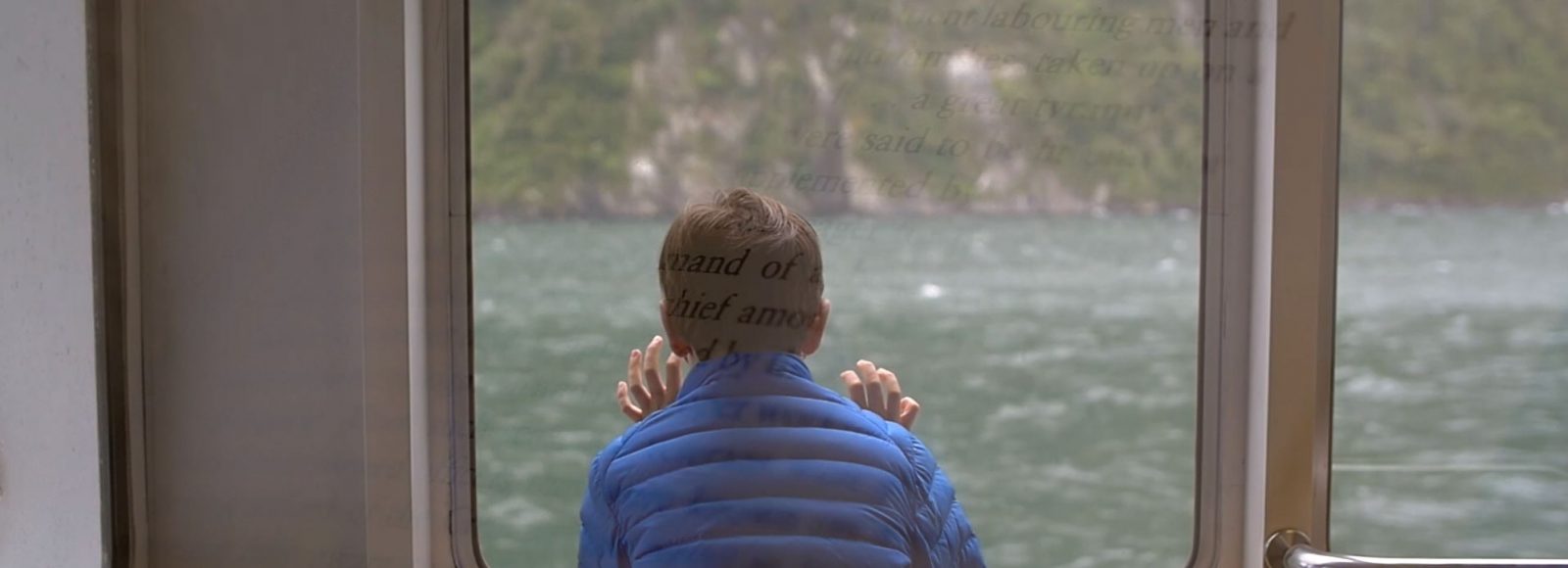

How might English literature count to those outside its traditional provinces of cultural and national appeal? How is it that a syllabus excludes by merely reflecting the image that a certain national elite in power around six decades ago projected on the discipline? Lying behind words such as “decolonial” and “diversity” are crucial concerns about how we identify through our reading, and how our reading might guide us in addressing current issues of social inequality and injustice. Those black British students who have not yet deserted the subject for more obviously “useful” ones have raised questions about how their reading speaks to their experience of the world. Many students now feel that they cannot “find themselves reflected” in standard “Englit” course content. Even in 20th-century courses, there are not enough texts by black and other minority writers. There are certainly insufficient theoretical approaches of non- European provenance – 18th-century black readings of Coleridge and Wordsworth, for example.

Yet in this gap between expectation and delivery lies the opportunity for English that the decolonial movement represents. Indeed, we might feel grateful to the students exercised by these matters for raising the question at all. They show us a new way of opening out English studies – or, some might say, of reasserting the importance of the kind of postcolonial work that some critics have been doing for decades, even if it was never in the interests of the mainstream properly to recognise it.

“If we open the canon,” the British Pakistani author Hanif Kureishi recently wrote, “we also open our minds.” On top of that, we reopen our field for a new generation of students who may well be drawn back to it if it speaks to their subjectivity and hopes of changing the world.

Elleke Boehmer is professor of world literature in English and director of the Oxford Centre for Life Writing, based at Wolfson College, Oxford. Her most recent book is Postcolonial Poetics.